The election which saw Indonesia’s social media-savvy and heavy metal-loving president Joko Widodo re-elected also saw bitter accusations of fraud from his long-time rival for the job. Just months later, that rival has joined government and the pair are posing for selfies. What does this mean?

When Joko Widodo (also known as Jokowi) won Indonesia’s presidential election earlier this year, supporters of his rival, former army general Prabowo Subianto, took to the streets and the ensuing violence left several dead.

Five bitter months since the vote

The election campaign had been angry, peppered with accusations of fraud, and it was only in the summer, in June, that Indonesia’s constitutional court finally ended the political uncertainty to uphold Mr Widodo’s win.

But just months after that, student protests hit the streets of Indonesia, prompted by a controversial and draconian criminal code being considered by parliament. They morphed into something bigger, an expression of anger and despair with the government. Protesters also rejected the passing of a new anti-corruption law which they thought undermined the country’s beloved anti-corruption agency.

Those protests also left several dead and, although the vote on the code was postponed, the bitterness is still evident.

Everybody watched to see how Mr Widodo would respond and what that might tell us about the state of democracy in Indonesia for the next few years.

In some ways, the answer came this week with the appointment of Mr Subianto as defence minister. Quite apart from being his rival in Indonesia’s two most recent presidential elections, he is a controversial figure with a tainted record on human rights.

Jokowi, as the president is known, was seen as a self-made “man of the people” when he first came to power in 2014 – mild-mannered, jocular and with a well-documented love of heavy metal music and taking selfies.

But the years have shown him willing to make harsh political compromises and, despite serious challenges to Indonesia’s stated values of religious tolerance and social cohesion in recent years, his priorities remain infrastructure, economic reform and political stability. This appointment can be seen as prioritising such goals as he eyes a tangible legacy at the end of his second and final term.

“You don’t see a lot of real reform-minded figures in the cabinet, the type of figures that would really give a sign to any liberals in Indonesia that the government is paying attention to issues of democracy and human rights,” says researcher Alexander Raymond Arifianto of the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies in Singapore.

“The government is just going to pave the way for status quo while they’re promoting all these higher priority projects in economy and infrastructure development.”

Who is the rival-turned-ally?

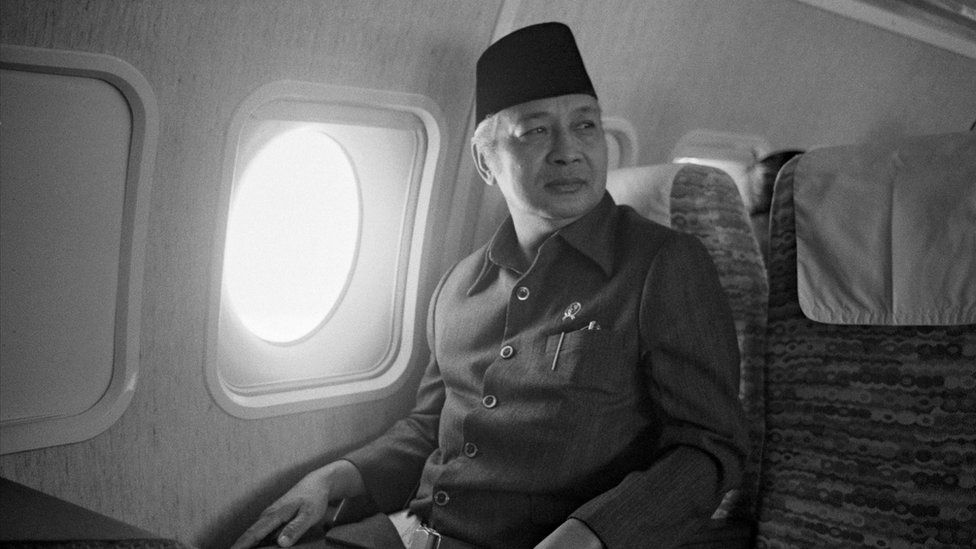

Prabowo Subianto, 68, was born into a family steeped in Indonesian political privilege, the son of Sumitro Djojohadikusumo, an economic whiz who held ministerial posts from the 1950s to the 1970s.

His father went into exile for a decade from 1957 because of his alleged involvement with a separatist group in the region of Sumatra. Mr Subianto followed as his family fled to a number of European cities, including Zurich and London.

Mr Subianto eventually married the second daughter of the late authoritarian president Suharto – a move some in the military have argued helped his swift rise.

But by that time, allegations were already swirling of his involvement in bloody military operations in East Timor.

He was eventually dismissed from the army for his role in the abduction and murder of student activists in 1998. His human rights record did not go unnoticed by the West, with the United States denying him visa in mid-2000s and 2014. Australia also once put him on a blacklist.

But Mr Subianto nevertheless made an extraordinary political comeback – although his four attempts to be leader ended in failure.

And Mr Widodo’s decision to add him to his cabinet, just months after his latest defeat, has dismayed many of the president’s supporters.

“[Jokowi’s] rival in the presidential election, who lost because the people rejected intolerance, anti-democratic [values], and human rights violations, is instead placed on an honourable position in the cabinet. We understand that there is a deep disappointment among Jokowi volunteers,” says Handoko, general secretary of Projo, a Jokowi supporters group.

So why did he do it?

“Prabowo is an intelligent individual who speaks multiple languages and will certainly be helpful when it comes to defence diplomacy,” says Aaron Connelly, research fellow on Southeast Asian politics at the International Institute for Strategic Studies in Singapore.

“But the biggest risk is that tension between Jokowi and Prabowo will not subside, but only get greater as the relationship is not built on mutual trust and respect.”

Yet the hope is that he will bring political stability to the president’s last term after five years of relentless attacks from his rivals, says Mr Arifianto.

Mr Widodo has made it clear that his priority is going to be infrastructure and economic reform, signalling his goal to be the country’s next “Father of Development”, a title once held by Suharto, Indonesia’s last dictator and his new colleague’s father-in-law. So such stability will be prized.

He also picked the co-founder of homegrown ride-hailing firm Gojek to head the education ministry and a media tycoon for a state-owned enterprises post.

But this is cold comfort for those worried about Indonesia’s direction when it comes to human rights and social inequality.

“Prabowo’s appointment sends a worrying signal that our leaders have forgotten the darkest days and the worst violations committed in the Suharto era. When Prabowo was at the helm of our special forces, activists disappeared and there were numerous allegations of torture and other ill-treatment,” said Usman Hamid, Amnesty International Indonesia’s executive director.

Mr Subianto has consistently said that he only followed orders from his chiefs and that he was scapegoated by the military, including by former army general-turned-politician Wiranto, who also happened to be Mr Widodo’s first-term security affairs minister

Mr Widodo’s strategy appears to favour compromise over confrontation – and that has resulted in a broad cabinet that involves several top generals whose potential bickering might create an enormous distraction to the president, Mr Connelly said.

But the choice of Subianto could pave the way for the politicisation of the armed forces and police, a feature of Suharto’s 32-year rule. As an example of this, there are regional leader posts currently held by active police officers, according to Titi Anggraini, director of Jakarta-based Association for Election and Democracy.

Military encroachment into civil spaces was among the features rejected by the student movement of 1998 – the student-led demonstrations that led to the fall of Suharto.

Mr Subianto did nothing to quell the violent protest to reject the elections result that erupted in his name.

The fear remains that his approach to resolve any tensions that might arise with the president could be just as unorthodox – despite the smiles for selfies. https://beritaberitaterbaru.com/